Across eight decades, the Ford Foundation has invested in innovative ideas, visionary individuals, and frontline institutions advancing human dignity around the world.

Learn more about our work in civil rights, education, arts and culture, human rights, poverty reduction and urban development and see some of our key foundation milestones below.

Civil Rights

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was an opportunity for the Ford Foundation to expand its support of academic studies on race relations and African-American educational institutions to include action-oriented grantees who sought to empower whole communities. Most significantly, Ford supported public defenders and the training of African-American lawyers. This innovative strategy became the framework for Ford’s advocacy for Mexican American, Native American, and women’s rights in the US, and for its role in bringing down apartheid in South Africa. By the 1980s, Ford was investing heavily in indigenous and cultural rights.

Since 1952, Ford Foundation grants have supported public defenders. In the 1960s, the foundation supported legal aid and litigation as a primary strategy to advance civil rights. This photo shows NAACP Legal Defense Fund Director Elaine Jones outside the Supreme Court on January 11, 1995, the day arguments were heard in Missouri v. Jenkins, a case concerning racial inequality in the state’s schools.

In 1968, Ford supplied seed funding for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), now often referred to as “the law firm of the Latino community.” This photo shows Jane Hilgen teaching her English class on the curb in front of the Edgewood High School in San Antonio, Texas, after she was suspended for her role in a student walkout protesting the school’s discriminatory practices. MALDEF intervened to ensure that Mexican-American students had access to equal educational opportunities.

Ford Foundation funding helped California Indian Legal Services implement a 1970 pilot program—the Native American Rights Fund (NARF)—to provide legal services to Indians on a national level.

Ford began supporting the Ms. Foundation in 1979 in order to advance women's rights in reproductive health and freedom, economic justice, and racial equality.

Education

Since 1950, Ford has been committed to strengthening educational institutions, leadership, and knowledge exchange around the world. The foundation seeded programs like Head Start and educational television, strengthened critical fields of research, and built new educational institutions. In 1956, the foundation contributed the largest ever influx of funding to higher education in the US, with $500 million in grants to private colleges and teaching hospitals. In the 1950s and 1960s, the fields of teacher training, business, and economics education were revolutionized thanks to another $47 million effort.

In 1952, the National Educational Television Center was founded with a grant from Ford, bringing iconic programs like Sesame Street and Mister Roger's Neighborhood to American living rooms—and paving the way for the establishment of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in 1970.

The United Negro College Fund, aimed at increasing the number of African American college graduates, was founded in 1944. A Ford grant in 1953 allowed the fund to expand, beginning a relationship that continued for decades. In 1973, Ford's first African-American program officer, Christopher Edley, assumed leadership of the Fund.

Ford's program in Economic Development and Administration sought to strengthen college and university teaching, and to support research on significant problems in business and education. Through fellowship and institution-building grants, Ford laid the groundwork for today's MBA.

In the early 1960s, Ford funded early childhood initiatives and education research that formed the basis for the federal Head Start program, which launched in 1965. Head Start, which provides early childhood education, health, nutrition, and parent involvement services to low-income children and their families, has served tens of millions of children—including Ford Foundation President Darren Walker.

The Ford Foundation’s pioneering, decade-long International Fellowships Program (IFP) supported advanced studies for social change leaders from the world’s most vulnerable populations. The program was established in 2001 with an initial grant of $280 million—the largest single grant in the foundation’s history. By 2013, more than 4,300 fellows from 22 countries completed graduate or postgraduate degree programs.

When it launched in 1962, the Ford Fellows program supported burgeoning efforts to build a more equitable higher education system, awarding fellowships to deserving young scholars from traditionally underrepresented groups to enable them to reach the highest levels of academia. The program, which continues today, has become one of America’s most prestigious and successful fellowship initiatives. Distinguished alumni include Juliet García, president of the University of Texas-Brownsville; KT McFarland, US deputy national security advisor; Condoleezza Rice, former US secretary of state; and Cornel West, civil rights activist and renowned author.

Arts and Culture

Since the 1940s, Ford has supported a wide array of arts organizations, including the Detroit Symphony and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Beginning in 1957, the foundation invested in individual talent and professionalized the arts sector by providing support and training to organizations including the Dance Theatre of Harlem. Worldwide, Ford’s arts programs have focused on cultural preservation and supporting diversity.

In the US, the foundation has helped establish major national arts projects, including the Lincoln and Kennedy Centers (completed in 1966 and 1969, respectively), and India Foundation for the Arts (1993). In the 1980s and 90s, the foundation’s Media Projects Fund supported media outreach on issues facing marginalized populations worldwide. Ford has promoted diversity and post-conflict reconciliation through museums, cultural festivals, and documentary films.

Beginning in 1959, Ford granted creative arts fellowships to individuals working in theater, music, visual arts, poetry, and writing. James Baldwin, Katherine Anne Porter, Norton Juster, and Saul Bellow were among the program's notable participants.

In the US, Ford began supporting arts and culture before any government agency did so. In 1963, the foundation made grants of millions of dollars to eight American ballet companies, including the School of American Ballet (SAB) in New York City, in order to strengthen professional ballet in the United States. The new funding helped transform SAB into a national organization that is today the premier ballet academy in the country.

Outside the US, grant making in the arts began in the 1950s with a focus on publication projects. By the 1960s, grants supported a range of cultural preservation projects, including the one pictured, documenting traditional performing arts in Indonesia.

Ford was a major underwriter for Eyes on the Prize, a 14-hour documentary television series covering the American civil rights movement from the 1950s to 1980s. The award-winning series reframed widespread understandings of the civil rights movement.

In the late 1990s, artists of all mediums articulated a need for space to exhibit, work, and foster Kenyan and East African art. The GoDown Arts Centre became the first Kenyan multi-disciplinary space for arts and host organizations representing a variety of art forms, allowing artists to freely express themselves and collaborate with one another.

Human Rights

During the Cold War of the 1950s and 60s, Ford supported intellectual freedom. Then, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, coups in Latin America prompted the foundation to adopt new policies for working in repressive societies. Launched in 1975, the foundation’s human rights program provided seed money to build new NGOs. Building on the legal strategies developed through the American civil rights movement, Ford helped support human rights law and watchdog groups around the world, including groups focused on women’s and indigenous rights.

Ford's work in South Africa began in 1953 with support for interracial dialogue. In 1973, a Ford-funded conference on legal aid proved to be a turning point, contributing to the growth of public interest law and other legal strategies to combat apartheid. At the same time, capacity-building programs trained a new generation of leaders for a post-apartheid society.

In 1969, a new military regime in Brazil ousted many social scientists from their academic posts. Concerned about creating a space for independent research, Ford staff responded by funding a policy think tank, the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP). One of the displaced scholars who helped create CEBRAP was Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who would go on to become president of Brazil.

In 1978, Ford helped establish the human rights organization Helsinki Watch, to monitor government compliance with the 1975 Helsinki Accords. After it expanded to monitor and spotlight human rights violations beyond the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe—establishing “watches” in Central America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East—in 1988 the organization was renamed Human Rights Watch.

In the 1990s, Ford grants supported the advisory council on the establishment of the United Nation's International Criminal Court, which entered into force in 2002. The Court oversees cases regarding international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

Ford helped lay the groundwork for the US-Vietnam Dialogue Group on Agent Orange/Dioxin, a bi-national humanitarian initiative aimed at developing practical responses to the continuing human and environmental consequences of Agent Orange use during the Vietnam War.

Poverty Reduction

Early on, Ford worked to address poverty through programs focused on population and overseas development, with emphasis on technical assistance, agricultural research, and government-driven planning. Later, this focus shifted to supporting civil society and NGOs. By the 1980s and 1990s, Ford was building the new field of microfinance and helping communities gain control over local resources and influence over local governance. In the 2000s, a holistic view of poverty’s causes and remedies led to a focus on helping poor families build assets.

Since its founding in the 1970s, Ford has supported the Children's Defense Fund (CDF), which advocates for children’s rights—paying particular attention to the needs of poor children, children of color, and those with disabilities. The CDF has worked for decades to ensure that all children are protected and have equal opportunities for healthy and successful lives.

Starting in 1976 with a Ford-funded project in Bangladesh, Muhammad Yunus offered small loans to disenfranchised people, especially women, to help them start their own businesses. This work developed into the Grameen Bank, a pioneer of microcredit, which has helped millions of people worldwide and earned Yunus a Nobel Prize.

In the early 1980s, Ford explored how US community development financial institutions might reach underserved populations. Beginning in 1984, Ford partnered with the Center for Community Self-Help in Durham, North Carolina, to expand economic opportunity for underserved communities by providing financing, technical support, consumer financial services and advocacy for those left out of the economic mainstream.

In 1994, Ford helped launch the Urban Trust of Namibia, an urban poverty research and advocacy organization that encourages democratic engagement and local governance.

After pilot projects succeeded in encouraging poor indigenous women in Peru to commit to formal financial savings, Ford supported a project called “C4-Proyecto Capital” that proposed linking inclusion in the financial system with social protection programs. Today, Proyecto Capital promotes the use of savings accounts in the formal financial system to complement conditional cash transfer programs in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Urban Development

The Ford Foundation’s early urban initiatives focused on education in the US and on urban planning abroad. By the late 1950s, programs were shifting away from buildings and infrastructure, and toward community engagement and economic opportunity.

To revitalize a disadvantaged Brooklyn neighborhood, Ford funded the first American community development corporation (CDC), the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. That grant catalyzed economic, cultural, and educational improvements in Central Brooklyn and launched the foundation’s future global efforts to support CDCs, including the Mombasa Municipal Council in Kenya.

In 1968, the Ford Foundation board approved a new approach—the program-related investment (PRI)—to use endowment funds to achieve social goals. In 1969, when a new tax act provided the legal framework for the strategy, Ford made its first PRIs to promote minority business development, increase the supply of low-income housing, and tackle environmental issues.

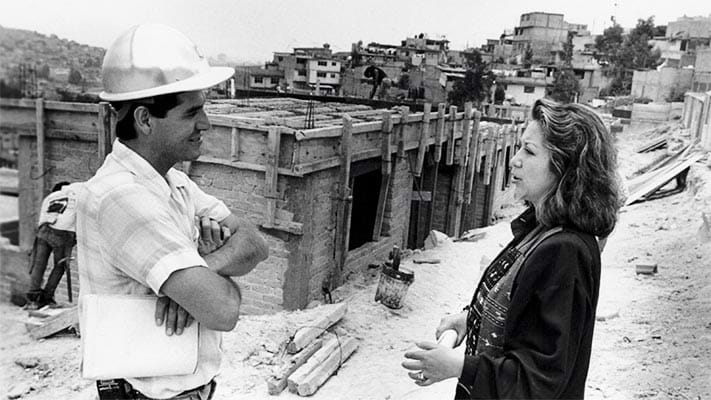

Beginning in 1990, the Center for Housing and Urban Studies was one of several Ford Foundation-funded programs to address community development issues in rural and urban Mexico.

In 2014, the foundation committed $125 million to Detroit’s Grand Bargain, an agreement between foundations, city officials, unions and retirees, and the state legislature to help resolve the city’s bankruptcy. The investment was designed to help Detroit turn the page on years of financial mismanagement and poor governance, and secure a better chance of strengthening democracy, participation, and opportunity for all of its residents.

Foundation Milestones

With the settlement of Henry and Edsel Ford's estates in 1947, foundation president Henry Ford II recognized that he had a great responsibility to respond to global issues. In 1948 and 1949, San Francisco lawyer H. Rowan Gaither led a wide-ranging study of problems to which Ford, the largest foundation in the world, might respond. Paul Hoffman—who had been economic administrator of the Marshall Plan in Europe—was chosen to be the first non-family president of the newly restructured international foundation. Here (left to right), Henry Ford II, Paul Hoffman, Chester Davies, Robert Hutchins, and H. Rowan Gaither meet in Pasadena.

With the settlement of Henry and Edsel Ford's estates in 1947, foundation president Henry Ford II recognized that he had a great responsibility to respond to global issues. In 1948 and 1949, San Francisco lawyer H. Rowan Gaither led a wide-ranging study of problems to which Ford, the largest foundation in the world, might respond. Paul Hoffman—who had been economic administrator of the Marshall Plan in Europe—was chosen to be the first non-family president of the newly restructured international foundation. Here (left to right), Henry Ford II, Paul Hoffman, Chester Davies, Robert Hutchins, and H. Rowan Gaither meet in Pasadena.

To clarify the division between the work of the Ford Motor Company and the Ford Foundation, in 1955 the foundation Board of Trustees—which included family members Henry Ford II and Benson Ford—decided to diversify the endowment portfolio by selling off its Ford Motor Company stock. This photo shows foundation president H. Rowan Gaither (pictured center) and a Ford Motor Company stock certificate.

Over the years, the foundation has supported more than 45 people and organizations who went on to win the Nobel Prize. They include the writer Saul Bellow, who won the prize for literature; Linus Pauling, a Nobel laureate in chemistry who was one of the earliest voices to warn of the threat posed by nuclear weapons; the International Labour Organization, honored with the Nobel Peace Prize for “introducing reforms that have removed the most flagrant injustices faced by working people around the world in the postwar period;” Amartya Sen, whose seminal work in development and welfare economics included research on preventing and combating famine; and Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to receive a Nobel in Economics, whose research into how people share common resources advanced the field of sustainability.

Designed by Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates, the Ford Foundation building opened in 1967. The building’s plan, with a now-iconic late modernist style and large garden atrium open to the public, was a stunning departure from the predominant architectural trends of the time.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the building a landmark in 1997. Beginning in late 2016, a renovation project will update and transform the foundation’s headquarters into the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice.

In 2016, the foundation began a major renovation and restoration project to reinvigorate the mission of its landmark headquarters building—ensuring that it works for far more people, is open to the public, and serves as an uplifting and energizing space for change. Upon reopening in 2018, it will be a contemporary, collaborative workspace that is open and green—and will be known as the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice.

Information and photos taken from the site: www.fordfound.org